Another follow up to the posting on LingYan Shan. One of the strangest things is that, at the top hill and beyond the gates of the temple, you suddenly find a bunch of hawkers. Whatever they are selling, they carry up the hill on their backs in the morning and they stake out their space for the day on a sidewalk or a dirt trail.

The top photo is a palm reader - one of 3 or 4 palm that were working the crowd. You can see his chart of palm topography lying in the dirt beside him. He seems to have the subject and his friends paying close attention.

Many of the hawkers are selling cheap jewelry. Others are selling religious and mystical trinkets. They spread their goods out on blankets on the sidewalks, like the ladies above.

Others set up carnival like games-of-chance, like the improvised ring toss shown above.

The hawkers go where the people are. Since most of the traffic is moving toward the scenic spots at the top of the hill, any space along the way is a potentially valuable storefront. Even if the space is on a muddy slope, like above.

Every business has it's managers and upper managers. The fellow above is, apparently, the CEO of a three-blanket jewelry store. The blankets were tended by a sales staff of two young women. The boss, you see, is hard at work in his office.

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

LingYan Shan Part II: The Monks

This is a brief follow up to the last post, about LingYan Shan. These are just some images that show the life of the Buddhist monks who live up on the hill. Above, you can see the golden robed monk passing through the walkways. (If this were a European church, this walkway would be called a cloister. It is a covered walkway, built along the edges of the buildings that form and enclosed courtyard.)

Slippers carefully stood in the windowframes to dry in the sun.

A doorway to living quarters of some sort.

The vegetable garden, outside the temple walls.

Robes, hanging as laundry to dry at the edge of the garden.

Slippers carefully stood in the windowframes to dry in the sun.

A doorway to living quarters of some sort.

The vegetable garden, outside the temple walls.

LingYan Shan

The opening of the Subway has made it much easier to travel to the far West side of Suzhou. Back in February, I took the city bus over to Tian Ping Shan. It took about an hour and a quarter. Now, it's just a 30 minute subway ride to the Mudu Terminal. From there, it is just a short bus or taxi ride to Tian Ping Shan or the old section of Mudu or any of the other attractions in that area.

LingYan Shan is another one of the "shan", or big hills, that form the Western limit of the Suzhou metropolis. (In Southeastern Indiana, these rocky hills would be called "knobs") LingYan Shan sits just to the South of Tian Ping Shan and is but a 10 minute walk from Old Mudu. The top of the hill is about 600 feet above sea level....which means it rises about 590 feet above the surrounding countryside. The tree- covered knob and the encircling strip of green space provide a place for local folks to escape from the city and enjoy some hiking. During the summer months, the cool shade of the trees provides a little relief from the heat of the concrete and asphalt.

LingYan Shan also attracts some tourists and religious pilgrims

At the top of the hill is an old Buddhist temple and along the paths upward are several shrines and such. The name - LingYan Shan - translates to something like "Spirit Rock Hill". It seems that the people of China have considered mountains to be sacred places since the dawn of their civilization. Over the last 2500 years or so of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, just about every hill higher than a speed bump has had some type of temple or shrine built upon it. The most famous of these are the Sacred Mountains of China, of which there are five...or four...or eight...or thirteen. (Depending on who is counting.)

The temple on LingYan Shan was founded sometime around 500 A.D. I don't know how old the current buildings are but I doubt they are nearly that old. The structures are made mostly of wood. The Buddhist tradition for the faithful is to burn offerings in cauldrons out in front of the buildings. Temple fires, in my understanding, were quite a frequent thing over the years.

From the foot of LingYan Shan you have two choices for going upwards. You can take the paved path or you can take the stairs. The stairs are the most direct way to the top, but require more exertion to climb. The paved pathway is no picnic, but takes a longer, winding route to reduce the incline. The stairs and the path intersect each other at a number of points along the way. You can see the stairs above and the paved path below.

The paved path features several prominent shrines and seems to be the more traditional way for pilgrims. You can see a monk in his yellow robes in the photo above. I saw one woman coming up the path wearing knee pads. She would take four steps, and then clasp her hands in a prayerful gesture to heaven. Then she would get down on her knees and prostrate herself in the direction of peak. She would rise to her knees with clasped hands and then low low again for a total of three times. Then she would stand up and walk four more steps, and then repeat the whole ritual. From the bottom of the hill to the top. Four steps at a time. It must have been a long day for her.

For those who have more to spend and less to atone for, there are easier options for getting to the top.

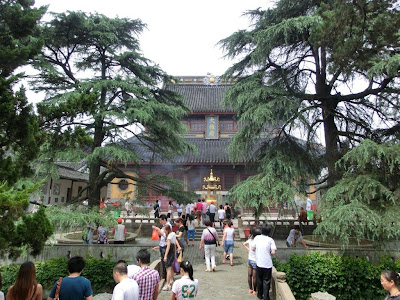

At the top, or nearly at the top of the peak is LingYan Temple. (By the way, there is another LingYan Temple, a much more famous one, near Mount Tai in ShanDong province.) The temple complex features a the main temple and a number of smaller side ones and a fairly impressive pagoda. The most interesting thing, though, is that seems to be a fairly large and active contingent of monks there. Most of the buildings seem to be dormitories and other living quarters. And you can see the monks out working on the hillside, tending to their gardens or trimming back the encroaching trees. LinYan Temple seems to be an active Buddhist community and much less of a tourist attraction than some of the other temples we've seen.

If you climb a little further from the temple, you can get a pretty good view of the surrounding city. That is what most people come for, I think.

The people will go anywhere and do anything to get a perfect view. I don't know if it is a fearlessness in the Chinese spirit or a lack of personal injury lawyers, but the local folks seem to have no problem to perch on the edge of cliff, as far out onto the rocks as they can go. It reminds me of the old photos of Civil War soldiers perched on Lookout Mountain. I think, maybe, the perfect view that the daredevils are looking for is one without 50 other people in front of them.

The photo below shows one of the shrines along the pathway to the top. It is difficult to see, but this small building covers images of the Buddha and some animals that have been carved into the natural rock. It's a grotto, I guess, though not a natural one in a cave or a cliff side.

The photo below is another shrine. Actually, it seems to be a small temple unto itself. This small shelter is surrounded by a walled courtyard. There is not room enough inside for more than 4 or 5 persons at a time.

Normally, I've sworn off photography inside of temples where people are actually worshiping. I'm following the rules of the Cathedral of Strasbourg; It's generally ok to snap photos, but none allowed during times of actual Mass. The problem, though, is Buddhist don't do a scheduled Mass. The temples are open to active worship at all times. So if there a lot of people around praying (and there usually are) then I try to be respectful.

This temple was small enough that there were no other people inside. So I figured fair game for photos. Also, the statue inside was remarkable in that it was so small - only about 10 to 12 inches high. With a very unusual gold statue involving a god of some sort and a fish. I'd guess there is a good legend which explains all this, but I don't know what it is.

You can tell the significance of a temple by the quantity of stuff burning in the offering pits outside. This small shrine must be a significant one, because there was a great fire pit of about 8 feet by 40 feet and a candle shelter that must have been 40 or 50 feet long. Much more was being burned here than at the temple at the top of the mountain.

This small temple is located in a midst of a large bamboo grove. The bamboo in the photo above are probably 5 or 6 inches in diameter and tower 50 feet or more into the air. Since bamboo groves are not that common in Indiana, I'd never realized that the plants create a fairly good canopy with their leaves. A bamboo grove is a rather cool and comfortable place to spend some time on a hot, sunny day. Especially after the equivalent of climbing the stairs to the top of a 50 story building.

LingYan Shan is another one of the "shan", or big hills, that form the Western limit of the Suzhou metropolis. (In Southeastern Indiana, these rocky hills would be called "knobs") LingYan Shan sits just to the South of Tian Ping Shan and is but a 10 minute walk from Old Mudu. The top of the hill is about 600 feet above sea level....which means it rises about 590 feet above the surrounding countryside. The tree- covered knob and the encircling strip of green space provide a place for local folks to escape from the city and enjoy some hiking. During the summer months, the cool shade of the trees provides a little relief from the heat of the concrete and asphalt.

LingYan Shan also attracts some tourists and religious pilgrims

At the top of the hill is an old Buddhist temple and along the paths upward are several shrines and such. The name - LingYan Shan - translates to something like "Spirit Rock Hill". It seems that the people of China have considered mountains to be sacred places since the dawn of their civilization. Over the last 2500 years or so of Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, just about every hill higher than a speed bump has had some type of temple or shrine built upon it. The most famous of these are the Sacred Mountains of China, of which there are five...or four...or eight...or thirteen. (Depending on who is counting.)

The temple on LingYan Shan was founded sometime around 500 A.D. I don't know how old the current buildings are but I doubt they are nearly that old. The structures are made mostly of wood. The Buddhist tradition for the faithful is to burn offerings in cauldrons out in front of the buildings. Temple fires, in my understanding, were quite a frequent thing over the years.

From the foot of LingYan Shan you have two choices for going upwards. You can take the paved path or you can take the stairs. The stairs are the most direct way to the top, but require more exertion to climb. The paved pathway is no picnic, but takes a longer, winding route to reduce the incline. The stairs and the path intersect each other at a number of points along the way. You can see the stairs above and the paved path below.

The paved path features several prominent shrines and seems to be the more traditional way for pilgrims. You can see a monk in his yellow robes in the photo above. I saw one woman coming up the path wearing knee pads. She would take four steps, and then clasp her hands in a prayerful gesture to heaven. Then she would get down on her knees and prostrate herself in the direction of peak. She would rise to her knees with clasped hands and then low low again for a total of three times. Then she would stand up and walk four more steps, and then repeat the whole ritual. From the bottom of the hill to the top. Four steps at a time. It must have been a long day for her.

For those who have more to spend and less to atone for, there are easier options for getting to the top.

At the top, or nearly at the top of the peak is LingYan Temple. (By the way, there is another LingYan Temple, a much more famous one, near Mount Tai in ShanDong province.) The temple complex features a the main temple and a number of smaller side ones and a fairly impressive pagoda. The most interesting thing, though, is that seems to be a fairly large and active contingent of monks there. Most of the buildings seem to be dormitories and other living quarters. And you can see the monks out working on the hillside, tending to their gardens or trimming back the encroaching trees. LinYan Temple seems to be an active Buddhist community and much less of a tourist attraction than some of the other temples we've seen.

If you climb a little further from the temple, you can get a pretty good view of the surrounding city. That is what most people come for, I think.

The people will go anywhere and do anything to get a perfect view. I don't know if it is a fearlessness in the Chinese spirit or a lack of personal injury lawyers, but the local folks seem to have no problem to perch on the edge of cliff, as far out onto the rocks as they can go. It reminds me of the old photos of Civil War soldiers perched on Lookout Mountain. I think, maybe, the perfect view that the daredevils are looking for is one without 50 other people in front of them.

The photo below shows one of the shrines along the pathway to the top. It is difficult to see, but this small building covers images of the Buddha and some animals that have been carved into the natural rock. It's a grotto, I guess, though not a natural one in a cave or a cliff side.

The photo below is another shrine. Actually, it seems to be a small temple unto itself. This small shelter is surrounded by a walled courtyard. There is not room enough inside for more than 4 or 5 persons at a time.

Normally, I've sworn off photography inside of temples where people are actually worshiping. I'm following the rules of the Cathedral of Strasbourg; It's generally ok to snap photos, but none allowed during times of actual Mass. The problem, though, is Buddhist don't do a scheduled Mass. The temples are open to active worship at all times. So if there a lot of people around praying (and there usually are) then I try to be respectful.

This temple was small enough that there were no other people inside. So I figured fair game for photos. Also, the statue inside was remarkable in that it was so small - only about 10 to 12 inches high. With a very unusual gold statue involving a god of some sort and a fish. I'd guess there is a good legend which explains all this, but I don't know what it is.

You can tell the significance of a temple by the quantity of stuff burning in the offering pits outside. This small shrine must be a significant one, because there was a great fire pit of about 8 feet by 40 feet and a candle shelter that must have been 40 or 50 feet long. Much more was being burned here than at the temple at the top of the mountain.

This small temple is located in a midst of a large bamboo grove. The bamboo in the photo above are probably 5 or 6 inches in diameter and tower 50 feet or more into the air. Since bamboo groves are not that common in Indiana, I'd never realized that the plants create a fairly good canopy with their leaves. A bamboo grove is a rather cool and comfortable place to spend some time on a hot, sunny day. Especially after the equivalent of climbing the stairs to the top of a 50 story building.

Sunday, July 29, 2012

Summer Smog

Normally, the Plum Rains come in June and last until the first of July. That's certainly the way it played out last year, when it rained most every day in the last three weeks of June. Then it got hot - stinking hot and humid.

This has been a strange summer, weather-wise. The June rains never really came. It stormed from time-to-time, but fell well short of the rainfall of last year. As June passed into July, the summer heat didn't really kick into gear. I wouldn't say that it was cool in Suzhou, but it was certainly cooler than normal. The daily temperatures topped out at about 90 degrees - 95 degrees at the most. And the humidity was merely oppressive, instead of downright murderous.

(While the U.S. Midwest was suffering through hotter than normal temperatures, many places in the rest of the world have been running a bit cooler than normal. Suzhou has. Northern Europe, too, has been having a cold, wet summer...at least according to my French, English, and Danish colleagues. )

The smog has been brutal, though.More often than not, it is hazy in this part of China. The high humidity is mostly to blame. Pollution contributes. But the hot, humid, continental air and the ocean breezes from the East are the main culprit. Blue skies are a rare thing. Normally the skies are steely grey and overcast in the mornings. The sun burns away much of the haze by afternoon. Then, the heaviness returns as the air temperature falls to toward the dew point in the evening.

This June and July, though, there have been days in which the haze lasts all day long. It's like being in a cloud. The sun is just a pale white-orange disk, if you can see it at all. And the colors of the world are a washed out to shades of grey, almost like at dusk.

The photos posted were taken on a day that was probably the worst we've seen in our time here. They were taken in mid-afternoon, at what should be the height of daylight. You can see how haze shrouds and obscures everything. I think, too, that the camera actually makes it look better than it does to the naked eye. (In the photos, I can see buildings that I don't remember being able to see on my own.)

Randomness

There has been no real excitement in Suzhou this summer, so far. Each day serves up its random annoyances and random pleasures. Here are some random photos in keeping with that theme.

The photo above is the bridge of the 11 arches down at Li Gong Di.

The next three photos are of some decorated barges that mysteriously appeared in JinJi Lake one week-end. Evidently it was a tourism thing, as there were barges from Taiwan and Singapore and all the touristic provinces of China.

The float above represents ShangHai. The famous Pearl Tower can be seen toward the rear of the barge.. The one below represents NanJing. It depicts the city's famous walls.

Below is a piece of public artwork from the lake shore on the South of JinJi Lake.

Finally, the photo below is just an old, narrow back-street in Old Suzhou City. There is barely enough room for two people to pass each other.

The photo above is the bridge of the 11 arches down at Li Gong Di.

The next three photos are of some decorated barges that mysteriously appeared in JinJi Lake one week-end. Evidently it was a tourism thing, as there were barges from Taiwan and Singapore and all the touristic provinces of China.

The float above represents ShangHai. The famous Pearl Tower can be seen toward the rear of the barge.. The one below represents NanJing. It depicts the city's famous walls.

Below is a piece of public artwork from the lake shore on the South of JinJi Lake.

Finally, the photo below is just an old, narrow back-street in Old Suzhou City. There is barely enough room for two people to pass each other.

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

MuDu

To the far West of Suzhou, on the flat lands at the foot of the hills surrounding Tai Hu Lake, is the old town of MuDu. For most of the last 2000 years, Mudu has been an independent village, separated from Suzhou City by miles of rural countryside. In the last 15 years or so, Mudu has been gradually absorbed by it's larger neighbor. Suzhou expanded outward, and the boundaries of the Suzhou New District crept relentlessly Westward toward Mudu. Mudu then became a bit of a posh suburb for Suzhou businessmen, and it expanded Eastward toward its larger neighbor. Today, the two cities are fused. You can't tell where one stops and the other starts. (Or at least I can't . I can't read the signs.)

Mudu prides itself on having history and architecture that rival Suzhou. In the heart of Mudu, in the historic district, are a series of gardens and mansions and temples and such. These are built along the main canal which, I would guess, served as the main artery of Mudu in the old days. Today, Mudu is a tourist attraction in its own right. But it is off the beaten path of the main tour groups which focus on the Humble Administrators Garden and Tiger Hill. When I visited, I saw a lot of people but not one other Westerner. My impression is that Mudu is pretty similar to a State Park in the U.S. It gets a lot of family visitors from the surrounding region on day or week-end trips. But it is not a Yellowstone that attracts people at the national and international level.

Mudu does seem to be a great place for a date. It has a gimmick with great appeal to young couples. There are ton of small shops that "rent" out historic costumes - outfits to make you look like a soldier or a scholar or a prince or a princess. The gimmick is that you can rent the costumes and then go off and search for a picture-perfect location to make your own photographs.

The shops don't provide the photographers...only the costumes. That is the brilliant part of the gimmick. All over Mudu you see young couples - one dressed up in a costume and the other fawning all over them taking hundreds of photos from every angle. They coo and giggle and lavish attention on each other....for hours. What is a date, if not an opportunity to coo and giggle and lavish attention.

The young lady in the photo below is an example. She is not just posing for a photograph, she is participating in courtship China-style.

The young lad in the topmost photograph is also an example of the costume-photo gimmick at work. The gimmick, you see, works not only on young couples. Parents also love to lavish attention on their young children. And young children love to dress up in costume and be the center of attention.

A tourist attraction would be incomplete without souvenir peddlers and street food. Mudu has it's share of both. Oddly enough, the main street of Mudu is named ShanTang Street, the same name as a similar tourist street in Suzhou. In both Shantang Streets, the pedestrian pathways are flanked with shops selling knick-knacks and food of all kind. In Mudu, Shantang Street gets narrower with each passing block until it becomes so narrow that two people can barely pass at the same time. (Of course, the locals still try to ride their e-bikes through this mess.)

The photo above shows one of the more popular offerings in the food stands on Shantang Street. Deep fried river crab. On a stick. It's a Chinese Crab Popsicle. It's all fried to a crunchy goodness. You can bite off a mouthful and chew and swallow - shell and bones and all.

Within Mudu are several classical Chinese gardens. Water - Stone - Greenery. The same formula you've seen before in the other gardens of Suzhou. But the gardens of Mudu are spacious feel a bit less cramped than the gardens in Suzhou City. One of them had room to include a traditional Kunqu opera stage. The photo below shows the stage, complete with actors in the process of a demonstration performance.

I'm out of gas....and can't put any words around the remaining photos. They are just different glimpses of Mudu. In Mudu, every time you turn your head it seems you are looking at a different picture postcard.

Mudu prides itself on having history and architecture that rival Suzhou. In the heart of Mudu, in the historic district, are a series of gardens and mansions and temples and such. These are built along the main canal which, I would guess, served as the main artery of Mudu in the old days. Today, Mudu is a tourist attraction in its own right. But it is off the beaten path of the main tour groups which focus on the Humble Administrators Garden and Tiger Hill. When I visited, I saw a lot of people but not one other Westerner. My impression is that Mudu is pretty similar to a State Park in the U.S. It gets a lot of family visitors from the surrounding region on day or week-end trips. But it is not a Yellowstone that attracts people at the national and international level.

Mudu does seem to be a great place for a date. It has a gimmick with great appeal to young couples. There are ton of small shops that "rent" out historic costumes - outfits to make you look like a soldier or a scholar or a prince or a princess. The gimmick is that you can rent the costumes and then go off and search for a picture-perfect location to make your own photographs.

The shops don't provide the photographers...only the costumes. That is the brilliant part of the gimmick. All over Mudu you see young couples - one dressed up in a costume and the other fawning all over them taking hundreds of photos from every angle. They coo and giggle and lavish attention on each other....for hours. What is a date, if not an opportunity to coo and giggle and lavish attention.

The young lady in the photo below is an example. She is not just posing for a photograph, she is participating in courtship China-style.

The young lad in the topmost photograph is also an example of the costume-photo gimmick at work. The gimmick, you see, works not only on young couples. Parents also love to lavish attention on their young children. And young children love to dress up in costume and be the center of attention.

A tourist attraction would be incomplete without souvenir peddlers and street food. Mudu has it's share of both. Oddly enough, the main street of Mudu is named ShanTang Street, the same name as a similar tourist street in Suzhou. In both Shantang Streets, the pedestrian pathways are flanked with shops selling knick-knacks and food of all kind. In Mudu, Shantang Street gets narrower with each passing block until it becomes so narrow that two people can barely pass at the same time. (Of course, the locals still try to ride their e-bikes through this mess.)

The photo above shows one of the more popular offerings in the food stands on Shantang Street. Deep fried river crab. On a stick. It's a Chinese Crab Popsicle. It's all fried to a crunchy goodness. You can bite off a mouthful and chew and swallow - shell and bones and all.

Within Mudu are several classical Chinese gardens. Water - Stone - Greenery. The same formula you've seen before in the other gardens of Suzhou. But the gardens of Mudu are spacious feel a bit less cramped than the gardens in Suzhou City. One of them had room to include a traditional Kunqu opera stage. The photo below shows the stage, complete with actors in the process of a demonstration performance.

I'm out of gas....and can't put any words around the remaining photos. They are just different glimpses of Mudu. In Mudu, every time you turn your head it seems you are looking at a different picture postcard.

Theresa's Tailor

The typical Chinese person is shaped very differently to the typical American person. And the clothing manufacturers here target the statistically average Chinese sizes. So, trying to buy clothes off the rack in China is a bit like hunting for unicorns. The odds are not very good. For example, I tried on a polo shirt once in a Chinese store....a size 3XL. It was too small for me by a mile. I tried on some shorts that fit in the legs and the waist but not in the seat. The pants were patterned for a person with no butt.

Most Westerners we know, when they need clothes, go to a tailor. You are guaranteed to get clothes that fit and the cost is comparable to store-bought clothes. (The cost is an out-right steal for custom tailored clothes.) Also, the tailors will make to whatever style you desire. Bring them a photo from a magazine and they will take a few measurements and then create an exact copy.

Theresa has found a tailor down in Shanghai that she likes....and has been throwing a bit of business to her. There have been a couple of dresses and a number of blouses made. Theresa normally selects patterns that the tailor has created. Things with a bit of an oriental flair to them. The photos here show a couple of examples.

Most Westerners we know, when they need clothes, go to a tailor. You are guaranteed to get clothes that fit and the cost is comparable to store-bought clothes. (The cost is an out-right steal for custom tailored clothes.) Also, the tailors will make to whatever style you desire. Bring them a photo from a magazine and they will take a few measurements and then create an exact copy.

Theresa has found a tailor down in Shanghai that she likes....and has been throwing a bit of business to her. There have been a couple of dresses and a number of blouses made. Theresa normally selects patterns that the tailor has created. Things with a bit of an oriental flair to them. The photos here show a couple of examples.

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

More Workers

Most of the landscaping and grounds keeping in Suzhou is done by hand. Most of it is done by elderly women. I don't know where these ladies come from; whether they are migrant workers or whether they are poor widows from the Suzhou area. But there are a lot of them. You see them in teams of 5 or 6, sitting on their knees, pulling weeds in the parks. All day they work, slowly moving across the lawn like sheep grazing. They wear hats of woven bamboo to shield them from the sun. If it is raining, they wrap the hat in a black garbage bag and keep on working.

The photo above was taken at our new factory on the East side of town. It shows some of the landscaping women on their lunch break, sitting in the shade of the bicycle parking shelter. They are making rope.

This team of women had spent the entire morning laying sod for the new lawn. The sod came rolled-up and tied by strips of thin plastic. The strips were about three foot long. The ladies collected all the strips and you can see them here twisting them to make a continuous length of rope. You can see that the lady in the foreground is using her right hip to pin down the plastic strips as she twists them. If you look closely, you can see a length of tightly woven rope emerging from her backside.

I've never seen anyone make rope by hand before. I figured that was a skill that disappeared sometime in the last century.

The photo above was taken at our new factory on the East side of town. It shows some of the landscaping women on their lunch break, sitting in the shade of the bicycle parking shelter. They are making rope.

This team of women had spent the entire morning laying sod for the new lawn. The sod came rolled-up and tied by strips of thin plastic. The strips were about three foot long. The ladies collected all the strips and you can see them here twisting them to make a continuous length of rope. You can see that the lady in the foreground is using her right hip to pin down the plastic strips as she twists them. If you look closely, you can see a length of tightly woven rope emerging from her backside.

I've never seen anyone make rope by hand before. I figured that was a skill that disappeared sometime in the last century.

Monday, July 16, 2012

Workers

The population of a Chinese city is a matter of fuzzy math. If you ask the population of Suzhou, you will get answers anywhere from 6 million to 13 million. For Shanghai, you will be quoted figures from 20 million to 35 million. Despite the fact that the Chinese authorities are meticulous in tracking residency and temporary residency, no one seems to know the population figures. The answers are algebraic.....6 million + x....20 million +x.

The "x" in these equations are the workers. The term "worker", by the way, is synonymous with the term "migrant worker". These are the army of people, mostly men, who build the skyscrapers and the subways and the apartment buildings and the sewers in Suzhou and Shanghai and Beijing and any other large city. It's easy to recognize them because they they usually carry their orange hard hat with them. If not, you can recognize them by their faces. Faces that are darkened by the sun and dried by the wind and the cold.

The workers are the men who did not score highly on their college entrance exams and, thus, failed to grasp the golden ring. In fact, they may not have had a chance to attend school at all. They come mostly from the farms and the small villages. They live in the cities, but do not reside there....."reside" being word with both metaphorical and a legal meanings.

All over Suzhou you can see the dormitories for the migrant workers. You can see them in the photo above; the mass-manufactured modular units (or porta-cabins as the Europeans call them). You find these all over town. Often, they are sited right next to the construction site. This is where the migrant workers live. Maybe not all of them, but a good portion. They are crammed together by the dozens into the equivalent of a tool shed that is steaming hot in the summer and freezing cold in the winter. They live like Spartans to minimize their living expenses. Most of the money they earn is going back home to the family.

Seriously, if you don't have a college degree then, statistically, it will be impossible for you to get residency in the city. And residency in the city, the city Hu Kou, is the big ticket. It means you have access to the best medical care and the best retirement plans and the best public transport and your children have access to the best schools. The funding for these benefits is locally generated - like the local tax base for a school system in the US. Big cities generate lots of funds and provide lots of benefits. Poor villages and rural areas, not so much.

Suzhou is a very nice city. Some visitors say it is better in many respects than any U.S. city. But you have to remember that it is a bit of an exclusive club. Not just anyone can join. The world outside the cities - in the farms and in the small villages - is a far, far different world.

Migrant workers come to the cities on a temporary residence permit to provide the labor which sustains the Chinese economic miracle. The migrant workers are the "vast labor pool" that everyone associates with China. In the construction jobs, almost always, they are men. They leave their wives and children behind. Hu Kou dictates that the children can only get access to public education in the their home town, in their legal residence. So if you are imagining the black-and-white photos of the 1930's migrant families in the U.S. - the workers and their families living together near the Hoover Dam construction site - forget about it. There are no families here. Only the fathers.

In other cases, the men are young and unmarried. They always have a home-town girl-friend that they desperately want to marry. But in order to get the family approvals, they first must be able to afford an apartment and a car and the other fixtures of stability and success that the bride's father and mother will demand. They work long hours in construction or as waiters in the Western restaurants or in the factories that assemble electronics. (When you hear horror stories of Chinese sweatshops assembling IPODs or cell phones, you need to remember that, in most cases, the workers WANT to work 16 hours a day to get all the overtime money they can. The faster they get the money, the faster they can go home and marry their sweet-hearts.)

In still other cases, the migrant workers are female. Some are old women that work at pruning trees and bushes and planting flowers. (At least they look old, after so many years of exposure to the elements.) Others are young girls come to work at the assembly factories for electronics. Others are young women that come to work in the massage parlors and Karaoke studios in hopes of meeting an affluent and available marriage prospect.

And so these migrants work for 11 months of the year far away from home; sending home every dime they can possibly spare. Family obligations overrule all else. Then, in the Spring Festival (aka Chinese New Year) they all travel home for two or three or four weeks of re-united bliss. Often, they trickle back days or weeks late. Often, they never return at all. (It's hell to be a construction manager in China during the Chinese New Year time.)

By the way, just for your reference. The average migrant construction worker in China makes around 1500 to 2000 RMB per month. (About $250 to $320). The average factory worker, maybe 2000 RMB to 3000 RMB per month (about $320 to $480).

The "x" in these equations are the workers. The term "worker", by the way, is synonymous with the term "migrant worker". These are the army of people, mostly men, who build the skyscrapers and the subways and the apartment buildings and the sewers in Suzhou and Shanghai and Beijing and any other large city. It's easy to recognize them because they they usually carry their orange hard hat with them. If not, you can recognize them by their faces. Faces that are darkened by the sun and dried by the wind and the cold.

The workers are the men who did not score highly on their college entrance exams and, thus, failed to grasp the golden ring. In fact, they may not have had a chance to attend school at all. They come mostly from the farms and the small villages. They live in the cities, but do not reside there....."reside" being word with both metaphorical and a legal meanings.

All over Suzhou you can see the dormitories for the migrant workers. You can see them in the photo above; the mass-manufactured modular units (or porta-cabins as the Europeans call them). You find these all over town. Often, they are sited right next to the construction site. This is where the migrant workers live. Maybe not all of them, but a good portion. They are crammed together by the dozens into the equivalent of a tool shed that is steaming hot in the summer and freezing cold in the winter. They live like Spartans to minimize their living expenses. Most of the money they earn is going back home to the family.

To understand the world of the migrant worker, you first need to understand the system of "Hu Kou". Hu Kou is the legal system in China that establishes where one's residency lies. With residency, Hu Kou also establishes what public benefits you are entitled to and where you kids must go to school and what medical care you are entitled to. I'd always thought (and I suspect most others think so as well) that China is a monolithic, national state. But it is truly as the name of the country implies - the People's REPUBLIC of China. It is, in fact, a very federal and very regionally fragmented administrative system. And your Hu Kou determines where in that fragmented system you get to play.

The Hu Kou system was established 50 years ago to prevent the chaotic rush of people to the cities from poor rural areas. In that aspect, it has been a success. The top tier cities in China are not surrounded by shanty-towns like in San Paulo or in Mexico City. But if you want to stay in the city, then you have to have Hu Kou. In a first-tier city like Shanghai or Beijing, or a second-tier city like Suzhou, the only way to get Hu Kou is to be born to parents with Hu Kou or to have a college degree and high job prospects. Seriously, if you don't have a college degree then, statistically, it will be impossible for you to get residency in the city. And residency in the city, the city Hu Kou, is the big ticket. It means you have access to the best medical care and the best retirement plans and the best public transport and your children have access to the best schools. The funding for these benefits is locally generated - like the local tax base for a school system in the US. Big cities generate lots of funds and provide lots of benefits. Poor villages and rural areas, not so much.

Suzhou is a very nice city. Some visitors say it is better in many respects than any U.S. city. But you have to remember that it is a bit of an exclusive club. Not just anyone can join. The world outside the cities - in the farms and in the small villages - is a far, far different world.

Migrant workers come to the cities on a temporary residence permit to provide the labor which sustains the Chinese economic miracle. The migrant workers are the "vast labor pool" that everyone associates with China. In the construction jobs, almost always, they are men. They leave their wives and children behind. Hu Kou dictates that the children can only get access to public education in the their home town, in their legal residence. So if you are imagining the black-and-white photos of the 1930's migrant families in the U.S. - the workers and their families living together near the Hoover Dam construction site - forget about it. There are no families here. Only the fathers.

In other cases, the men are young and unmarried. They always have a home-town girl-friend that they desperately want to marry. But in order to get the family approvals, they first must be able to afford an apartment and a car and the other fixtures of stability and success that the bride's father and mother will demand. They work long hours in construction or as waiters in the Western restaurants or in the factories that assemble electronics. (When you hear horror stories of Chinese sweatshops assembling IPODs or cell phones, you need to remember that, in most cases, the workers WANT to work 16 hours a day to get all the overtime money they can. The faster they get the money, the faster they can go home and marry their sweet-hearts.)

In still other cases, the migrant workers are female. Some are old women that work at pruning trees and bushes and planting flowers. (At least they look old, after so many years of exposure to the elements.) Others are young girls come to work at the assembly factories for electronics. Others are young women that come to work in the massage parlors and Karaoke studios in hopes of meeting an affluent and available marriage prospect.

And so these migrants work for 11 months of the year far away from home; sending home every dime they can possibly spare. Family obligations overrule all else. Then, in the Spring Festival (aka Chinese New Year) they all travel home for two or three or four weeks of re-united bliss. Often, they trickle back days or weeks late. Often, they never return at all. (It's hell to be a construction manager in China during the Chinese New Year time.)

By the way, just for your reference. The average migrant construction worker in China makes around 1500 to 2000 RMB per month. (About $250 to $320). The average factory worker, maybe 2000 RMB to 3000 RMB per month (about $320 to $480).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)